Jelly Belly

Can cancer be stranger than science fiction? Can we guys get over our "toughness" and ask for help when it counts?

I’ve got a new stomach story to tell.

One that is by turns scary, strange and even silly. One that I think has lessons about men's mindsets and how we can live healthier, fuller lives.

The story starts, in a way, with a picture I posted earlier this month of me and my bigger belly. I talked about how I'd been gaining weight, how I'd been feeling ashamed about being less slender than I used to be, and that I'd come to a certain peace about it.

I gave myself some grace for engaging in self-soothing eating over the last several years—which were pretty hard on me, along with most everybody else in the world.

I talked about the possibility of men blending strength and surrender in the right amounts. I said that maybe a soft belly was needed for hard times.

And I don't disavow any of that.

But there's more to the story.

There was even more going on in that belly than I realized.

***

This past two weeks, I had a series of trips planned to conferences to talk about “The Tough Guy Show” and how men can age in healthier ways.

I was going to speak at a gathering of ski lift professionals in Massachusetts, then lead a session at the On Aging conference in Orlando, then head to Bend Oregon for another ski conference.

The first leg of this tour was challenging but satisfying. There were skeptics in the room of about 350 people, 95% men, when I gave a keynote talk on how we need to “F*ck The Tough Guy Show” and create healthier workplace cultures in the ski industry.

A few guys sat with arms crossed, declining to join me in “doing the 6Cs.” These are gestures I’ve developed for six practices that help us evolve our sense of manliness: Curiosity, Courage, Compassion, Connection, Commitment and Contemplation.

Still, my message about busting out of a confined masculinity seemed to resonate with most of the audience.

By the end, virtually everybody was standing up and doing a “liberating masculinity” dance with me—the 6Cs set to Sade’s “Why Can’t We Live Together.”

As I shimmied with the ski fellas, I didn’t realize I’d need to take my own medicine in a matter of days.

Between Massachusetts and Florida, I had a pit stop in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. There I spent Easter weekend with my friends Temple and Ben. Much of the time was focused on taking care of Temple's kitty Tove, who had an infection in her side. She needed multiple stitches and days in what Ben dubbed the “Cone of Recovery.”

I soon joined Tove among the poked and prodded.

***

The morning of my flight to Orlando from North Carolina, I woke with intense pain in my abdomen.

Maybe it's gas, I thought. Or it might be a muscle strain. Lord knows I’ve experienced plenty of both those maladies.

But the pain lasted all Monday, including after I checked into a hotel in Orlando and got ready for bed. I started worrying there could be something else going on. My first thought was appendicitis. A quick Google search seemed to confirm my symptoms. And told me that more than 50% of untreated cases of appendicitis result in death.

That got my attention. So did the fact that I started feeling feverish, and that the Cleveland Clinic says: “You might never think about your appendix until one day it starts hurting.”

An important caveat here is that I have a history of psychosomatic episodes. For example, more than once I’ve thought I was having a heart attack–and it was a panic attack. In fact, just this February, I went to the ER for what I thought was heart trauma. Yet, my heart got a strong bill of health. It was anxiety.

That incident helped me reset my mental health. But it also cost close to $5,000.

So when I called my wife to talk about my abdominal pain, my fear of appendicitis and my inclination to go to the ER, Rowena was skeptical.

Finally, we compromised. Together we called the advice service of Kaiser Permanente, our health care provider.

We spoke to a doctor who said it was hard to tell whether I had appendicitis without a physical exam. It would be prudent to get to an Emergency Room, he said.

So I did.

At about 11 pm Monday night, I arrived at an ER of AdventHealth. The doctor on call palpated my belly–ouch! And had me get a CT scan. When the results came back, he said it looked I had a ruptured appendix and needed to be admitted to the hospital.

I was sad to miss my talk on how men can age in happier, healthier ways. Yet I also felt relief. I had a clear diagnosis with a good prognosis.

I also felt good that I’d applied one of the lessons I planned to speak about at the conference: men often ignore signs of pain and don't get life saving care. I was taking my own abdominal pain seriously here.

And it was proving out–just not quite in the ways I expected.

***

The story got scarier at this point.

My main doctor at the AdventHealth Celebration—I’ll call her Dr. J—came into my room with less-than-celebratory news.

There were some “concerning” issues in the CT scan, she said. It didn't look exactly like a burst appendix. Additional “spots” in my abdomen suggest, in fact, a “malignancy.”

Malignancy? Whoa. “Does that mean cancer?” I asked?

Yes, she said. That was a possibility. We needed another CT scan, as well as an MRI and a blood test to be more sure.

I tried to be even-keeled at this news. But it also terrified me. And I admitted as much to my wife and our dear friends Jason and Colette, who we pray with every weekday morning.

Intellectually, I know that cancer isn’t necessarily a death sentence. Rowena recovered from breast cancer about 10 years ago. My mom survived it as well. Other friends have similar stories. But having grown up in the 1970s and ‘80s, when treatments were far less effective, the notion of a malignant tumor triggered a primal fear.

***

That worry reached a fever pitch Tuesday afternoon when my nurse, Rachel, stood at her mobile computer terminal and told me that results from a CT scan of my chest were in.

“What do they show?” I asked her? I knew the test could signal massive trouble, if masses were found above my belly as well.

“You’ll have to wait for the doctor,” she replied. Rachel explained that her training didn’t equip her to interpret test results to patients–and she didn’t want to give an inaccurate impression.

I understood. But as I watched her read the computer screen, I figured she knew enough to know if it looked like curtains for me.

I scrutinized her face, searching for any sign of emotion. Pity, hope, anything!

At that moment, a message popped up on the computer screen. She got a note saying the chest CT scan looked fine. Rachel told me as much.

Relief washed over me.

“Yay!” I yelled.

We both laughed.

***

As Tuesday wore into the evening and I awaited the MRI that would give us the most definitive imagery of my belly, my mindset shifted. My soul stirred.

The knee-jerk dread at hearing I may have cancer evolved into something more like perspective. I found I could face the C of cancer, partly with the help of the 6Cs.

“Deal with it with presence,” I wrote in my journal. “With self-compassion, with vulnerability, with courage, with wisdom, with connections and community.”

And courage did rise in me–a blend of strength and surrender.

I would not cower in this moment. And I would sink into what it all might mean.

It struck me that if I was facing an imminent end, I had plenty to be thankful for.

“I’ve lived a pretty fucking great life,” I told Rowena on the phone.

Our two kids, Julius and Skyla, are wonderful. They are more or less thriving in college. My marriage to Rowena, 23-years-and counting, is stronger and more satisfying than ever.

I have amazing family and friends. I love my colleagues and the different communities I participate in. I get to do purposeful work that gets my juices flowing.

And here in the hospital, the free apple juice was flowing. Along with an “endless supply” of ginger ale, nurse Rachel promised. Plus the warm blankets that can’t help but make one feel cozy and cared for. Hospital “hygge”!

I meditated–the C of contemplation. I thought about the inspiring lives and deaths of my parents. I wondered about seeing them and other beloved relatives after dying.

I thought of my late father-in-law, Carl Richie, who chose to take himself off life-support a few years ago. On his deathbed, Carl said he was “curious” about meeting Jesus.

I thought of a dear friend, Helen. She once mused that when we die, the light we’ve generated during our lives remains and adds to all the light created before us. Would my light persist?

***

The C of curiosity also served me as things took a strange turn Tuesday.

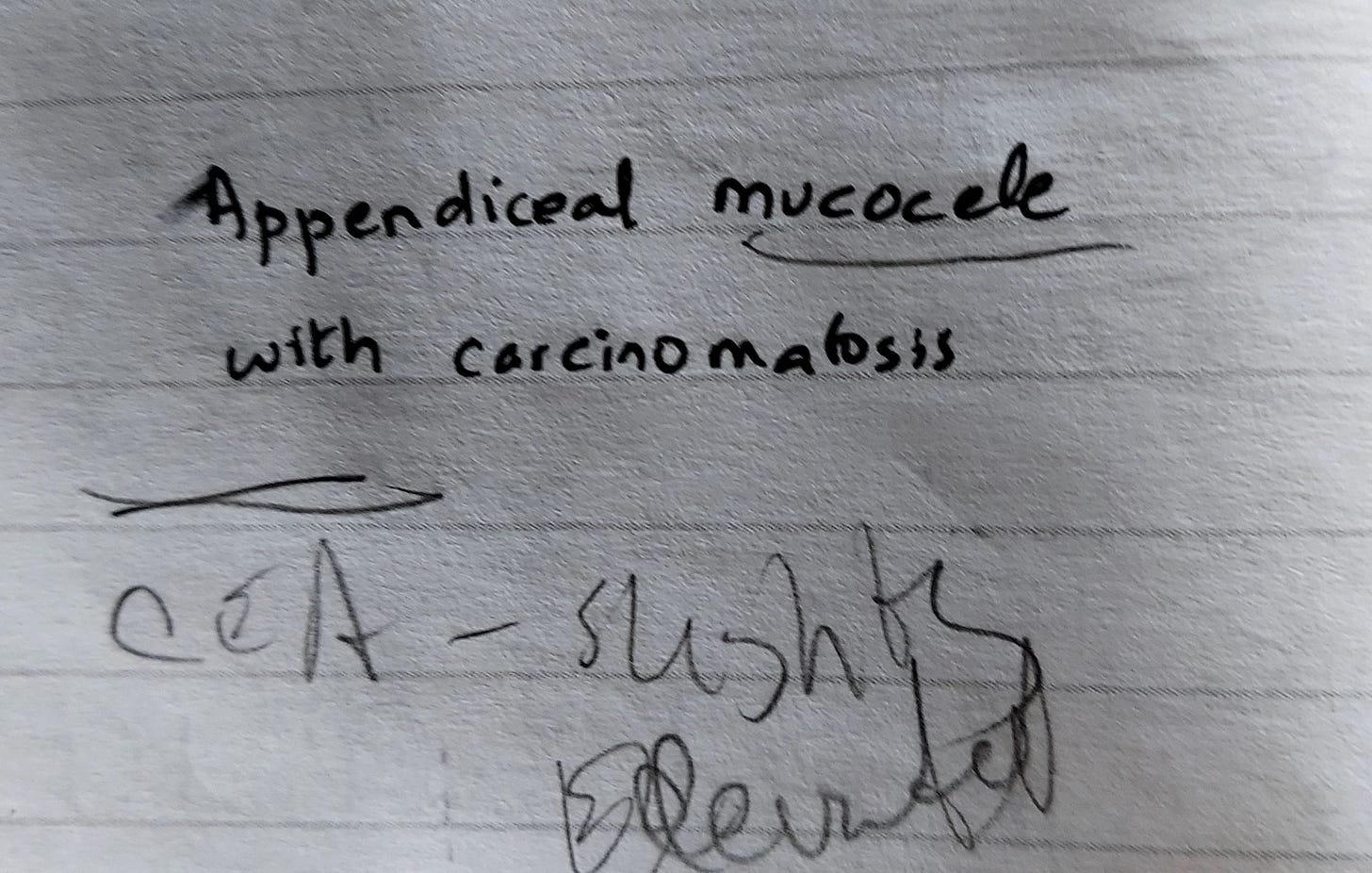

Dr. J came in and said the tests suggested I had something called “appendiceal mucocele with carcinomatosis.”

What??? I asked her to write the words down in my notebook, so strange were they.

She explained that cells associated with my appendix had gone haywire and begun producing unnecessary mucus. And that these cells had spread through my abdomen.

“Don’t cancer cells cause tumors,” I asked? I meant, tumors that grow like crazy and take over healthy tissue.

Not necessarily, I learned. The cancer cells Dr. J was talking about cause trouble not so much by reproducing themselves but by producing mucus.

Before we went any further, Dr. J said, she wanted to speak with an oncology surgeon and get their opinion.

I felt like I was in a science fiction story. Cancer means more than runaway cell reproduction? It can mean building up a blob of sorts in the belly? A sliming of the stomach region?

***

Along with the wildness of this new possibility came optimism. Could this be a more treatable situation than a traditional cancer?

Dr. J was cautious about offering any prognosis. But the specialist doctor I saw next was more confident about providing a promising outlook.

Oncologist surgeon—call him Dr. G—stopped by my room Wednesday in surgical scrubs, complete with shower cap-like head covering.

He said it is likely I have a condition along the lines of what Dr. J described. For full confirmation, a biopsy would be needed. But it looked to him that I have “pseudomyxoma peritonei” or PMP.

Yes, it’s cancer. But Dr. G painted a picture far less perilous than my stereotype of “malignancies.”

The main threat of PMP is the massing of mucus, such that it squeezes the digestive system and potentially crushes other organs.

Yet these rogue cells stay in the abdomen, and can be removed in a surgery that is taxing but typically successful.

You slice open the belly, remove the appendix, possibly part of the large intestine, as well as a layer of fat known as the “omentum” where the cancer cells migrate. Then you wash the abdomen with chemotherapy and sew the patient back up. About a quarter of the time, PMP comes back.

But if it does, Dr. G said, “you can do the procedure again.”

***

At this point, I started getting punchy about my paunch.

Dr. G recommended I go home to San Francisco for the operation, which requires a week’s stay in the hospital and about two months of recuperation overall.

So I started packing up my stuff and making arrangements with Rowena and Colette to fly home Wednesday night.

And my dad humor kicked into high gear. The situation became just silly.

The scientific community is partly responsible. After all, when you visit the Cleveland Clinic’s page for PMP, they say it is typically called “jelly belly.”

I’ve got a bunch of mucus machines in my gut.

I’m living a personal rerun of Ghostbusters, with nearly invisible entities slinging slime across my tummy.

My omentum has got all the wrong momentum.

The surgery could be slimming.

Or my fave:

It’s not my stomach–it’s snot, my stomach!

***

I took this selfie of myself in my hospital room, wearing these absurdly stretchy gender-neutral disposable underwear the hospital staff gave me.

The meaning of this photo to me is not that I was wrong to be kind to myself when I thought my bigger belly was a function of comforting myself amid hard times. It’s more that I see other lessons.

One is that we men, especially, must take signs of health trouble to heart. Or to the hospital. Research shows, for example, that men often ignore chest pain or other indicators of a heart attack. We try to tough it out, which can literally kill us.

I’m glad I paid attention to my abdominal pain, before my jelly belly blob did extensive damage or killed me. Jelly belly, for all it’s comical nickname, can be fatal.

But perhaps the biggest lesson I’m learning is to see things with new eyes. There’s something about worrying about dying that makes you really appreciate living.

I am in a state of bliss about all my besties. My friends across my years—from my childhood in Buffalo to college to career to life in San Francisco.

They are so with me.

One of my oldest pals, Elise, discovered that PMP affects just 1-4 people in one million. “Just confirms what I’ve always known…you’re one in a million!"

Writer friend Rachel pointed out that PMP has been described in the medical literature as “indolent”—a reference I think to the way these cells cause little to no pain directly. She made me laugh with the notion of a lazy cancer.

“The nerve!” Rachel wrote. “To be rare AND indolent!”

She went on to offer an array of assistance options. And she was part of a flood of folks saying they stand ready to help.

“Prayers to you Ed,” Baki texted. “Remember you have a big support group.”

I know we all die alone. But we don’t often don't talk about how much we can die “with” loved ones.

***

Maybe this hopeful view will change if my prognosis changes. I go in for more testing tomorrow in San Francisco. My situation may be more dire than it currently seems. And maybe soon I’ll have to face my mortality more intensely than I have this week. Someday I will face it all the way–I will die!

But for now, I feel very alive. I feel close to loved ones and hopeful about moving through this health challenge.

I feel excited about my work to help us break out of limited notions of manliness, freeing men and everyone around them to lead healthier, happier, more soulful lives.

So that's my new stomach story.

Right now, I'm feeling perfectly full.

I cried when Temple gave me an update this morning. You were in my dream last night. It was so sweet. I was giving you some friendly pecks on the cheek. Then I read your post and I laughed - omentum momentum! Thinking about coming to visit you and Rowena sometime this summer if it's not too much. Sending you lots of hugs my friend.

This is what makes you a great storyteller, men's health advocate extraordinaire, and wonderful guy.