Scrooge, Fathers, Holidays and Love

A "Twin Substack" with my pal Kate Mangino on how to deepen bonds with dads this holiday season

One of the timeless stories of the holiday season has to do with a strained, distant father-child relationship.

Many people think A Christmas Carol is about ghosts, or an incorrigible man.

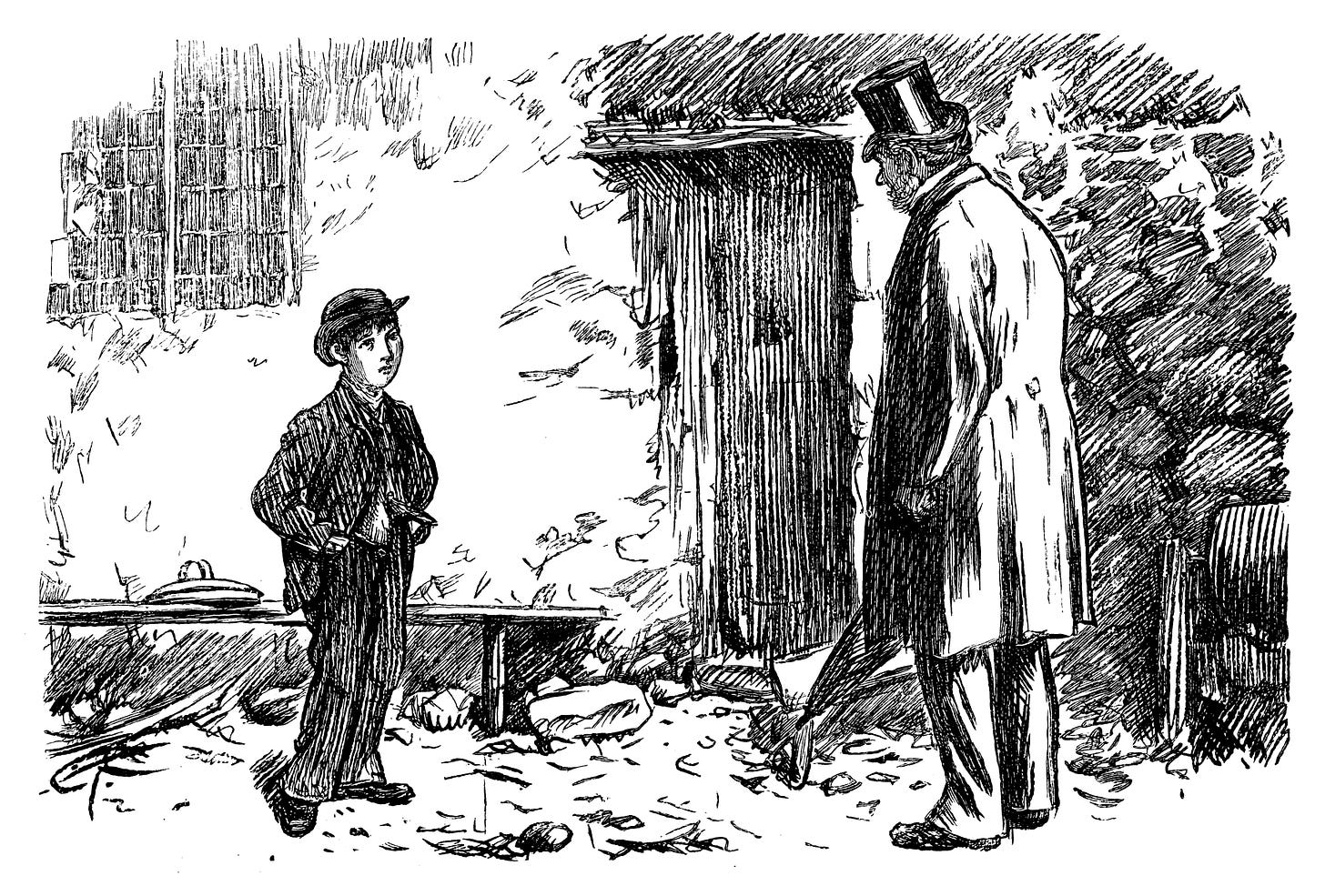

Actually, the root of the story is about a father who acts coldly to his son, Ebenezer Scrooge, sending him off to boarding school and leaving there even during the holidays. Largely as a result, Scrooge becomes bitter and miserly.

Unfortunately, many real-life fathers today aren’t close to their children either. More than a quarter of adults say they have been estranged from their fathers.

Disconnection from fathers isn’t surprising, given the way men have been socialized to suppress emotions, focus on being providers and protectors, and feel obliged to discipline children with a firm hand.

But as Dickens’ classic Christmas story reminds us, poor relationships between fathers and children result in lasting wounds.

For some, the holiday season can be a time to begin to heal. Fathers and children can take several steps to repair torn bonds or strengthen existing ties.

My friend and colleague Kate Mangino decided to do what we’re calling a “Twin Substack” on this topic. We’re starting the post the same way and then sharing our individual perspectives. Read on for my thoughts on strengthening father-child relationships over the holidays, and click here for Kate’s thoughts.

Tough to be tender

Connecting deeply with our fathers isn’t easy for many of us.

The “confined masculinity” that has shaped our views for centuries tells us that men aren’t supposed to show feelings. Boys–and men–aren’t supposed to cry. And dads are supposed to see themselves as breadwinners first. Sure, it’s great if we make it to our kids’ soccer games and dance recitals. But moms are slotted into the role of primary nurturer–the parent who grows closest to the child.

No wonder that just 6 percent of adults have been estranged from their mothers.

The fact that many more people experience estrangement from their fathers also has to do with how dads have been expected to be chief enforcers in families. That duty has often come with a belief that we have to be tough on kids to raise them right–”spare the rod, spoil the child.”

The result is many fraught, shallow father-child relationships.

From temper to tenderness

That pretty much captures what my relationship with my own dad was like for my childhood and much of my adult life.

My dad was scary when I was a boy. He could be super fun, and he supported me and my siblings in school and sports. But he also could be judgmental and had an explosive temper. I remember him pinning me against the wall and screwing up his face, biting the tip of his tongue in rage.

My dad’s bouts of anger contributed to anxiety I’ve wrestled with throughout my life.

But our relationship evolved. My dad softened in his middle age and older years. He became more affectionate and humble.

I also changed. I got more comfortable being vulnerable and honest about our relationship.

This culminated in a beautiful moment about three years ago. I’d experienced a mild heart attack, followed by panic attacks. I saw a counselor to treat the panic and anxiety. And when she heard me talk about my dad’s fits of fury, she suggested I may have to “grieve my childhood.”

That led me to write about my dad’s temper and its impact on me. When I showed the draft to my dad, part of me reverted to that scared 10-year-old son. I was afraid he’d blow up at me.

He didn’t. Instead, he said this: “I can see how my anger would have led to problems for you. I’m sorry.”

I thought my dad might continue speaking, to provide an excuse for his troublesome temper — as human beings so often do when acknowledging a flaw.

But no. Not another word. A pure-hearted, gracious apology.

I spoke up, saying that his outbursts may not be the only cause for the anxiety I’ve wrestled with. And then I realized I was called to speak words to honor his:

“I forgive you, Pop.”

The exchange seemed to wash a deep wound in both our souls. Healing our psyches in ways we didn’t expect.

We only grew closer in the years that followed. My dad died in early September. It was sad to lose him. But mostly I have felt gratitude and relief. Relief that he is free from physical pain and the emotional suffering of missing my mom, who died 10 years earlier.

And gratitude for the gifts he gave me. These included courage he showed facing death and accepting hospice care. And the gift of us having reconciled our differences. For the loving, close bond we had.

There were no big things left unsaid between us. He and I were at peace, content with each other.

How do I do this?

How can more of us get to that point in our relationships with our fathers? How can we connect better, heal old hurts, strengthen our bonds?

Three keys:

Realize fathers want to be closer. Dads, especially us older fathers, may seem uninterested in communicating on a deep level. But this is largely a function of the “confined masculinity” that has shaped us. Men can–and want to–break out of that emotional straightjacket. That’s been my experience working with a variety of men of different ages and professions.

It’s also what the data shows. A Pew Research survey from before the pandemic found that 63% of dads said they spend too little time with their kids. And my Substack Twin Kate co-wrote an article showing how many fathers leaned into caregiving during the Covid lockdowns–and don’t want to go back to less-involved roles.

Start with strengths. When encouraging dads to open up, begin by asking them to share about positive experiences and emotions. Maybe ask “What are you proudest about?” Followed by “Who have been your heroes?”

Once the juices are flowing, you can graduate to more painful and poignant topics. Like: “Can you tell me about your toughest day?” “What’s most surprising as you look back on your life?” “What do you want to be remembered for?” and “When were you proudest of me?

Be vulnerable yourself. The best way to invite your dad to let down his guard is to let yours down first. Being the first to be candid. You might begin by sharing your happiest memory of your dad. Or what qualities of his you most admire. Or what makes you most proud of him.

You also can share ways you’ve felt hurt or disappointed by your dad. Bringing up scars can trigger shame or prompt a father to lash out defensively. So acknowledge your own role in any conflicts. Avoid overstating your dad’s responsibility. And come from a place of vulnerability if you can. I tried to do this with my dad–saying something like “I felt a lot of fear as a kid when you exploded in anger, and I think it contributed to anxiety later on.

The rewards of speaking up authentically and without defensiveness can be great. They were for my dad and me.

Even Ebenezer could change

When fathers and children open up their hearts, profound joy and richness are possible.

Both Kate and I felt a surprising depth of connection with our dads before they passed away this past year or so.

You may be able to feel as much with your father this holiday season.

Scrooge himself shows the way. He didn’t reconcile with his father. But after his night of ghostly lessons, Scrooge took it upon himself to tend to his relationship with his estranged nephew, Fred. He visits Fred and his wife on Christmas day.

What he experienced at their home, according to Charles Dickens, is what’s available to us when we strengthen bonds of love: “Wonderful party, wonderful games, wonderful unanimity, wonderful happiness.”

Thank you for sharing, Ed. Love your dad's humble acknowledgment and the healing that brought you both. Acknowledgment, apologies, and forgiveness are not easy - perhaps the most courageous act of love there is, and they have the power to bring such peace. Your story is a testament to that. Hope you feel the peace you deserve today. Merry Christmas to you and your family. <3

Beautiful and helpful!!!