Day One of Chemo; Rowena Writes Another Poem

It was scary and sucky. It was sublime and sounded like laughter. It made me think I can heal by transforming cancer cells with "understanding and compassion." Plus my lady publishes another gem.

Still Here

My chemo adventure began yesterday.

I’m already learning lessons. Some more pleasant than others. The day included terror and disgust. But also flashes of insight and courage, more than a little laughter and moments of peace.

Overall, I take heart in the fact that I’ve started. And that I feel largely myself.

The me I’ve worked to develop–who looks to a variety of teachers, who tries to face fears, who blends yin and yang energies.

In more ways than one, I’m still here.

***

The day opened with the Prayer Porch ritual I have with my wife Rowena Richie and dear friends. We shared what was on our “prayer hearts” and ended with a reading. The one I picked felt perfect for the day ahead.

It was a short passage from Thich Nhat Hanh, the deceased Vietnamese monk and peace activist. The passage is from Nhat Hanh’s book, How to Fight–a series of meditations that align with my attempt to reframe cancer healing as more than merely combat. The book has a pair of boxing gloves on the cover. But the readings almost invariably offer guidance that is more about hugging than it is about hitting.

The passage from yesterday was titled “Killing Anger.” It read, in part:

“A Brahman asked the Buddha, ‘Master, is there anything you would agree to kill?’ The Buddha answered, ‘Yes, anger. Killing anger removes suffering and brings peace and happiness.’

Naht Hanh continued: “We ‘kill’ our anger by smiling to it, holding it gently, looking deeply to understand its roots and transforming with understanding and compassion.”

You go, Thich.

His words speak to how I want to treat the cancer in my body. It struck me you can view cancer cells as “angry”--lashing out blindly and uncontrollably, causing trouble and suffering.

I also love the idea of “transforming” cancer cells. Not obliterating them entirely. That is impossible, actually. I prefer to imagine dissolving them, alchemizing their destructive structure into elementary chemical building blocks. Molecules that will remain.

That might be used to build something new and healthy in my body. Or that might leave my body to participate in growing something else. Or that may simply be.

Later in the day, Rowena and I researched how chemotherapy works, and the entire term “transforming with understanding and compassion” seemed to fit. Chemo drugs can interact directly with cancer cells’ DNA–the genetic material at the heart of these unhealthy little creatures. In that sense, the medicine comes to understand the cancer–know it intimately.

Chemotherapy works largely by inducing what’s called “apoptosis”--programmed cell death, or cell suicide.

Aggressive? Violent? Perhaps. But also compassionate. In the sense that these cancerous cells have no real future. If they continue to go down their rampaging path, they will kill me, their host.

And then they, too, will die.

***

With Thich Naht Hanh in my heart, I headed off to Kaiser Permanente’s 8th floor chemo infusion center. Our prayer porch partner and pal Colette agreed to drive Rowena and me.

During the drive, I experienced a spat of existential fear. My friend Liz, an MD Anderson cancer researcher, had texted that morning to interpret what her colleagues had found in my biopsy.

It wasn’t the best news.

Kaiser’s pathology department had declared my appendix cancer to be “grade 2”--just one click up from the least aggressive malignancy. But we sent the tissue sample to the cancer specialists at MD Anderson for a second opinion, given that mucinous adenocarcinoma is a rare cancer.

Liz texted that MD Anderson pathologists had found “grade 2 to 3” cancer cells. I imagined my survival chances dropping with this news. From somewhere above 60 percent at 5 years out to somewhere lower. I didn’t know how much lower.

And it may be impossible to pinpoint them precisely given the specifics of my case, which includes a relatively small amount of cancer spread in my belly.

But I was spiraling in the car with Colette and Rowena.

So I called Liz. Bless her heart, she answered, between patient visits.

“It could be worse, right? With a finding of goblet cells?” I said in a pleading voice.

Yes, Liz confirmed. And in a calming voice, she said my treatment plan remained the right one–three months of chemo, abdominal surgery, then more chemo.

Whew. I settled back in the car seat.

***

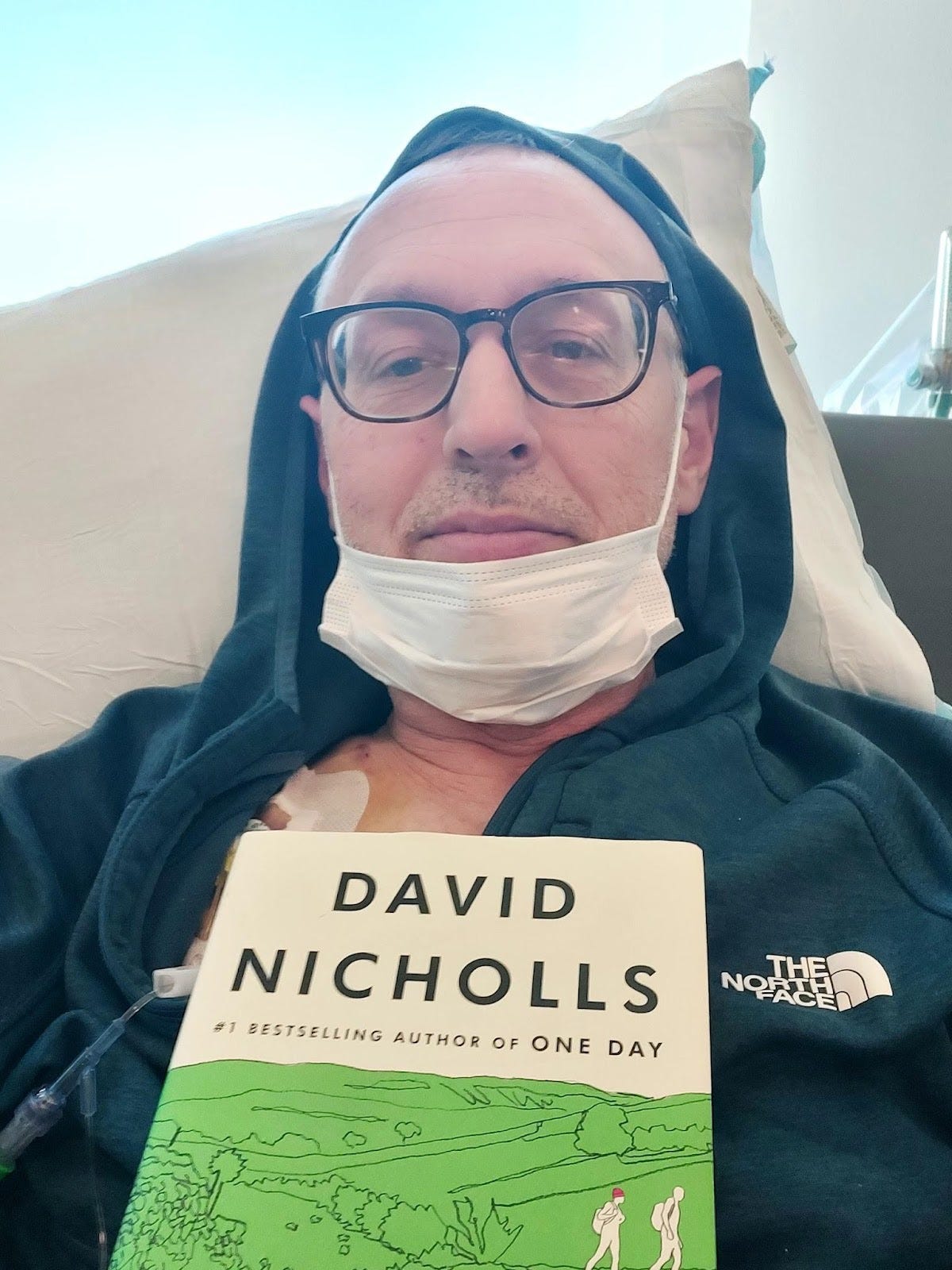

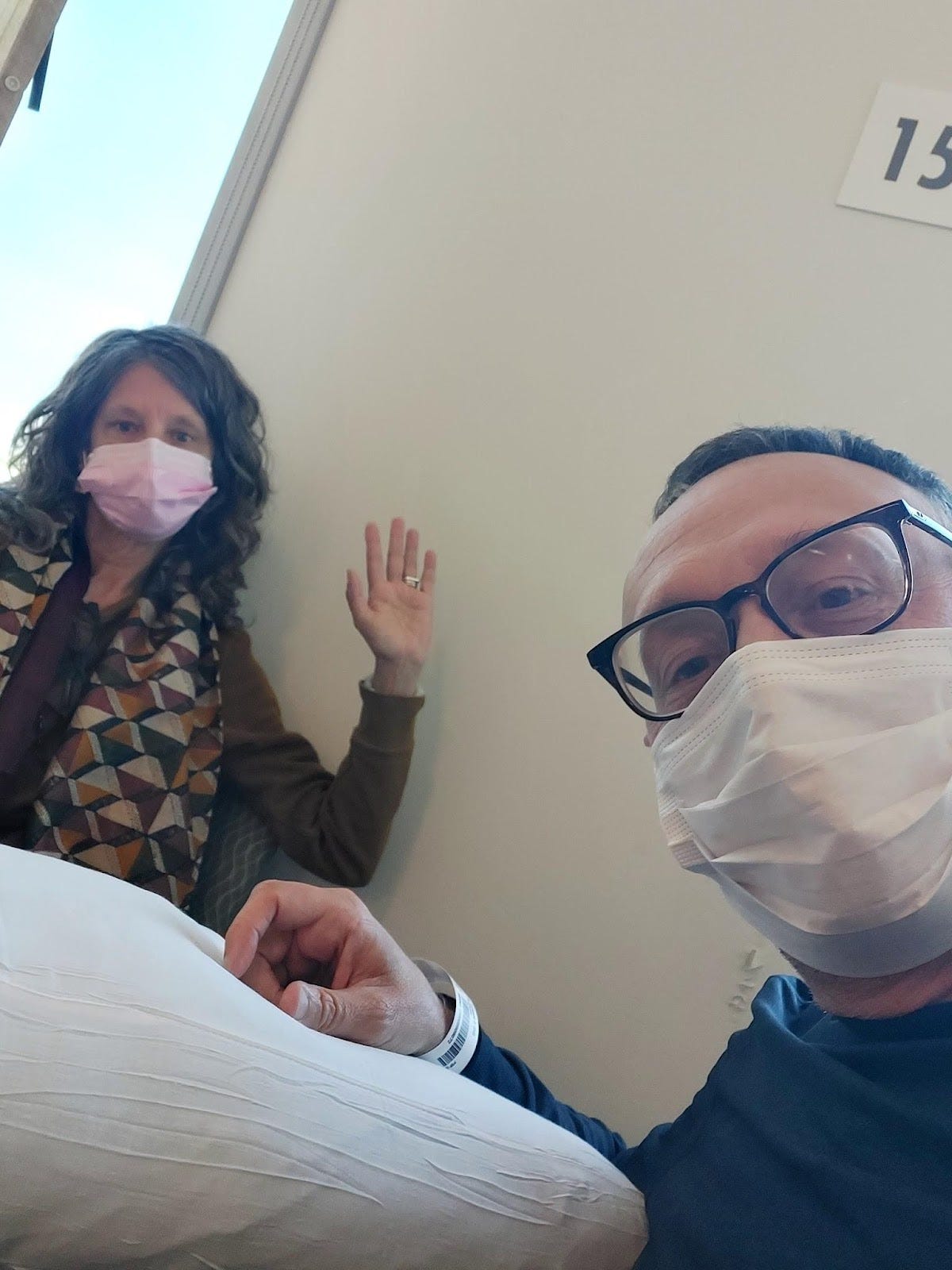

Pretty soon, I was sitting in the chemo infusion chair. An electric recliner with heating and massage features. Rowena sat next to me, as nurse T described the chemotherapy procedure and its risks.

The more nurse T talked, the more it felt like the scene from the movie Contact that I wrote about recently.

I may experience a drop in energy. I may experience neuropathy–numbness in my fingers. I may have trouble breathing as fluids build up. I may experience nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. Worse side effects include an allergic reaction that can ruin the lungs–the very thing that killed my father-n-law five years ago.

But I steeled myself in my chair, doing my best Jodi Foster impression.

“I’m Ok to go. I’m Ok to go. I’m Ok to go,” I said in my head.

And we went. T poked a needle through the skin into my chest port. The chemo drug oxaliplatin started flowing into my veins.

Rowena and I held hands. Tears welled up behind the surgical mask she wore.

“I love you,” she said.

I don’t think I’ve ever felt such devotion, affection and care.

“Love you too,” I replied.

***

I didn’t notice anything regarding the medicine for about an hour.

During that time, Rowena and I read You Are Here to each other. This is a rom-com novel by David Nicholls, given to me by my college pal Laura.

There’s a rough parallel to the story and my current cancer situation. A love story. And an arduous journey–a hike clear across England that takes nine days.

One character in particular, Marnie, is hilarious. She is simultaneously copyediting a book about an orgy, trying to come out of a Covid-era shell and flirt effectively.

Rowena and I found ourselves laughing out loud time and again.

Laughter may be the best medicine. And I don’t regret guffawing in the cancer chair.

Still, our cackling felt slightly inappropriate for an infusion ward that was decidedly sombre.

About six other patients were sitting in their own chairs, cordoned off in square units by curtains. Most didn’t have guests like I did–a perk of the first chemo treatment only.

And several of the other folks with tubes connecting to IV drip bags were young. A thin 20-something woman covered in tattoos. A fit fella who looked to be in his 30s.

The two of them are part of a trend. Younger people are increasingly getting cancer. At 57, I’m also part of a growing incidence of appendix cancer among Millennials and Gen Xers.

The disturbing developments may have to do with changes in our collective diet–such as consuming more ultra-processed foods.

And then the food in me took a disturbing turn.

About an hour into the infusion, my tummy started to rumble. My intestines gurgled–loud enough for Rowena to hear.

T was on lunch break, so I reported feeling queasy to her replacement, Nurse P. She gave me an anti-nausea pill.

And I rolled the chemo infuser station with me to the bathroom.

What followed was not pleasant in the least. It was one of the most extreme bouts of diarrhea I’ve ever had.

Yuck. And challenging to wipe myself with tubes dangling around my body.

Shitty. Yet somehow cathartic.

I felt better soon after. And I’m very happy to report I haven’t experienced the runs since that very fast moment.

***

It struck me that enduring nausea and dealing diarrhea get at what it means to “fight” cancer.

I’m not landing blows on the microscopic mischief makers in my midsection. The medicine is doing some version of that. I’m just weathering the storm. The feelings of not being fully well.

The phrase “Still Here” seems to capture this epiphany. In a couple of ways–one archetypically feminine, one archetypically masculine.

The yin, the archetypal feminine, is stillness. Just sitting still as the poisons wash through my body. Being present. Now. And here.

The yang, the archetypal masculine, is assertiveness. Persistence in the face of pain and discomfort.

I’m still here, motherfuckers.

I’m trying to be receptive and to resist at the same time.

I’m aiming to be the Port of Frauenheim, a being who welcomes what arrives and actively gambles on a better future.

And I wonder if we men, especially, would be healthier if we embraced such an integrated mindset.

***

My friend, author Sean Harvey, has a simple way of speaking to this point. He says men suffer, because they are human. All human beings experience trauma at some point in their lives. But most men haven’t had access to the range of tools and emotions for healing that women (and non-binary folks) typically have.

Freedom to feel our pain, to treat ourselves with compassion, to ask for help and lean on others. These have been quashed in men traditionally.

Boys don’t cry. Man up. Grow a pair.

Many men today are hurting, confused and feeling left behind. Men raised to be stoic, self-made and successful individually can come across as rigid, cold and isolated in a world asking them to be agile, warm and connected.

In recent years, we’ve had long-overdue reckoning over sexism. And racism or other forms of exploitation. Men, especially white men, have held the most power. And many have abused their power.

But it’s also true that most men don’t have a lot of power. In their jobs. In terms of wealth and status.

As men struggle and feel as if they aren’t fully seen, many of them–young men in particular–are turning to extreme, misogynistic influencers like Andrew Tate.

Yet those right-wing, manosphere icons fail to offer sustainable, healthy solutions. The recent trial of rapper Sean “Diddy” Combs shows how the playboy, strongman image of masculinity easily translates into stomach-turning violence.

This is the argument I made in an op-ed article co-written with Ronald Levant and Christopher Kilmartin and published recently in the Akron Beacon Journal.

Thankfully, more and more men are now remembering, recovering their full humanity. Quietly, out of the headlines, many men are learning to speak about their emotions.

Men are actively rejecting hyper-masculinity and combining traditional male strengths such as conviction and a duty to protect the vulnerable with a willingness to be vulnerable themselves, to take their wounds seriously, to intentionally build bonds with others.

This is happening in surprising places.

Such as among the ski lift professionals I have worked with over the past several years. Men now saying “Fuck the Tough Guy Show.” Tough-minded corporate attorneys also are working to reinvent masculinity in their profession and their lives. Professional athletes, actors and successful entrepreneurs also are on the front lines of this shift to a more complete, soulful way of being a man.

…

I’m not all the way there myself. But I’m working on it. And this cancer experience is my latest training ground.

I’m trying to survive this disease. Even as I’m trying to surrender to the spiritual charge I’m feeling, to the mystery of this brush with mortality.

And I’m letting myself be supported by those around me.

OMG am I being supported. With cards, calls, texts and money–an astounding $56,000 that surpasses our GoFundMe goal. With cookies and broth from Mary. Broth and stew from Michael. An original watercolor painting from my sister-in-law Melanie.

Plus an email from my old Buffalo pal Courtney. Not only did Courtney make my day by praising my writing (still working on needing less extrinsic motivation!), but she stopped me in my tracks with a picture she shared.

“I stumbled across the photo below (of babies, I might add--how were we all this young!?) at the exact moment the FrauenTimes email with your beautifully written addendum arrived,” Courtney wrote.

It felt like another minor miracle making its way into my cancer journey.

The photo dated to the early 1980s. I sat on a couch with Courtney’s sister Becky, our friend Kathy, and Courtney.

It felt like several lives ago. It reminded me that I’ve lived many chapters, experienced many adventures and much love across my 57 years.

Courtney also quoted poignant lyrics from a Genesis song that we listened to back then: “Home By The Sea.”

Images of sorrow, pictures of delight

Things that go to make up a life

I am satisfied with the life that I’ve made, that’s been made for me. It’s been full.

And I want more from it.

I’m still here.

Starfish: for Julius

By Rowena Richie

I’m wearing your Alaska Starfish Co. sweatshirt. Your hooded souvenir fits me like a glove. Were you twelve when you fell in love? Denali, glaciers, eagles, a wedding whetting your appetite for faraway picturesque adventures?

Where you are now, New Zealand, today is tomorrow, your summer is our winter. Where I am now, San Francisco, our winter is our summer, dawn is breaking through a fog.

Starfish. Can't they regrow their limbs? Let's learn from them: non-attachment, adaptation, life with high and low tides.

I wish upon a shooting starfish you were here. I miss your care, conversation, musicality. I could use a Julius hug. Is Dad's cancer diagnosis stealing focus from your wilderness, waterfalls and study-abroad? I'm worried I'm wearying you, just twenty-two.

Watching the dawn, I tuck into your sweatshirt, a proxy for hugging to come. No doubt this cancer trial is a training ground. I'm digging deep. I find calm, remembering. I grew a new heart when you were born.

Ed (and Rowena),

This piece is such an inspiring post to read. It so captures the spirit of Ed that I got to meet for the first time at the Big Tent Summit a few weeks ago. I deeply appreciate your yin/yang framing of what you're going through (and HOW you're going through it). You get massive extra brownie points for quoting a Genesis song (also one of my faves of theirs)!! I also loved Rowena's poem. I can so empathize with that missing of your child who'll never be a child again.

Thanks for sharing your journey with us. I am praying for a full recovery for you Ed, as if it's already a certainty. Any way I can be of support, you know where to find me. ❤️🙏

You two are writing a very imPORTant book. Love that you are bringing us in and along. Love youse.